There are always people, or sometimes moments, that shape us. They influence who we become, how we see, and what we choose to make of our lives.

At 18, I decided to seriously pursue photography. I signed up for a class at Northern Virginia Community College, a fairly new school whose photo department was just getting started. I was among the first students in the first class taught by the newly hired head of the three-person department, a young woman named Joyce Tenneson.

Joyce pushed us hard, sometimes to the point of irritating me. Her critiques could be tough, but they made us better. After a couple of semesters, I asked how I would determine my style. Her response was not to concern myself with it. “Just keep taking photos, your style will find you.”, she said. Years later, as I reviewed my growing body of work, I recognized that I had indeed developed a style of my own.

Among Joyce’s assignments was to create a self-portrait. I don’t recall what I came up with at the time, but she continuously pursued self-portraits of her own and became famous for them. Now world famous, she has published 30 photography books, mostly her portraits of women, and always instantly recognizable by her style.

In a 2024 interview, her advice remained consistent: “I very strongly believe that if you go back to your roots, if you mine that inner territory, you can bring out something that is indelibly you and authentic, like your thumbprint. It’s going to have your style because there is no one like you.”

In 1988, famed portrait photographer Arnold Newman was celebrating fifty years in photography. What a thrill it was to be assigned to do a three-day interview and portrait for a photography magazine.

As a photography student, I had studied Newman’s work and admired his masterful environmental portraits. I had his books on my shelf and had always aspired to create portraits as artistic as his. And now I was to spend days in his company, in his home, his studio, and over dinners, as he spoke passionately about art and photography.

He stressed the importance of art history, saying that every photographer should know what has come before, saying, “How can you do something new if you don’t know what’s been done?”

And he spoke about style. “You can fake style to an extent, but then it’s only going to be an imitation of something if you aren’t inventive enough. Style is a result, not a name. Eventually, even those with little talent will develop a style, which most of the time is the influence of someone else because they don’t have the imagination. There are those people who can create and add to our knowledge and those who take our knowledge and make it work.”

Then came the hard part, quietly loaded with intimidation. It was time for me to do a portrait of the master of portraiture himself.

Those three days changed me. I’ve never doubted that my own photographs are stronger because of his influence.

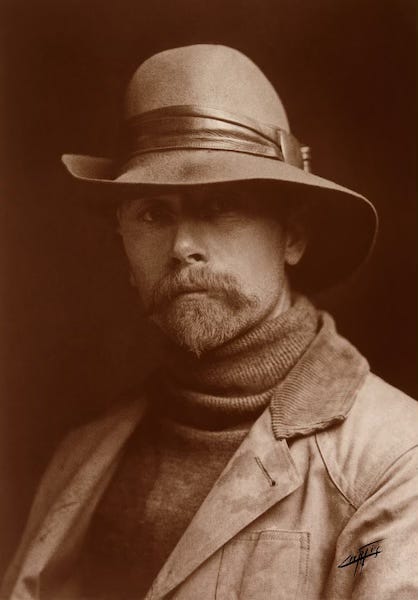

There was one more photographer who had a significant influence on me, though I never met him. He died when I was just 2 years old. Edward S. Curtis spent decades documenting the lives of Native Americans, beginning in 1895 and continuing until 1927. His body of work consists of more than 40,000 photographs, as well as motion pictures and sound recordings.

Curtis endured years of arduous travel to capture authentic glimpses of indigenous life amid rapid cultural assimilation. He has been criticized for romanticizing and stereotyping the lives of the Native Americans he photographed, yet his work remains monumental in scope and significance.

For me, Curtis’s work represents what Newman meant about knowing what’s been done. Through his photographs and books, and even in prints I’ve collected, I’ve absorbed his sense of purpose. A century later, I’ve tried, in my own way, to pick up that baton. My documentation of Native Americans falls far short of his achievement, but I hope it contributes something meaningful, in my own style, shaped by all who came before.

A common thread among all three of these photographers is the portrait. Whether it’s Joyce’s luminous portraits, Newman’s studies of artists and thinkers, or Curtis’s monumental documentation of Native peoples, each sought to portray humanity through the camera. That same impulse continues to inspire me to make images that connect and speak to who we are.

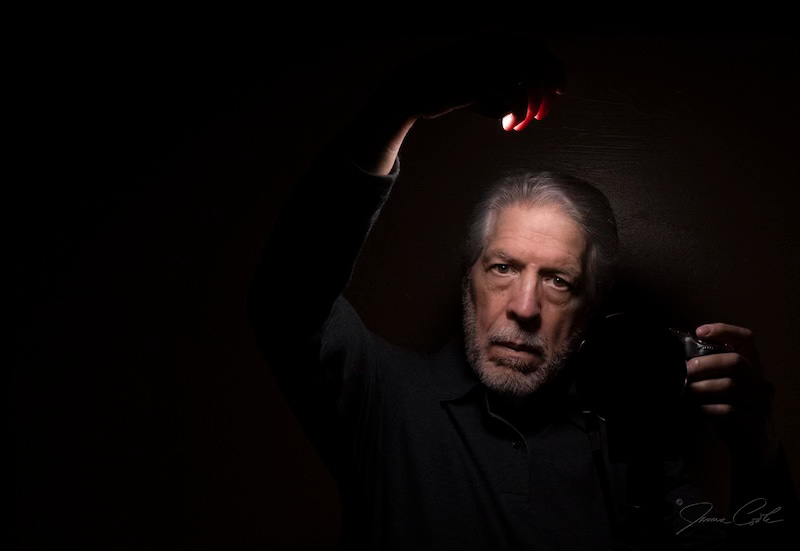

In closing, and in the spirit of Joyce Tenneson, Arnold Newman, Edward Curtis, Picasso, Van Gogh, and many others, I’ll leave you with a self-portrait of my own.